CS180 -- Automata Theory

Assignments

Assignments will be listed below as they

are assigned.

"Suggested exercises," for the purpose of this page, are suggested problems for

you to work out, generally with answers in the book. Suggested exercises are not

to be handed in.

Assignments are to be written out and handed in, and

often entail what are called "exercises" in the text (sorry for any confusion

that may cause!). For those of you who have a second edition,

differences in page or problem numberings with the third edition will be given

if there are any.

Suggested exercises: On page 83: Exercises 1.1, 1.2, and 1.4b and d.

Assignment #1 (DUE: Thursday 9/5/19; no collaboration):

- Page 26, Exercise 0.3.

- Page 27, Problem 0.11.

Note to those who may have the second edition: The problem listed as 0.11 in the

third edition didn't exist back then (Problem 0.11 in the second edition became Problem 0.12 in the third). Here is Problem 0.11 (as in the third edition) written out:

Let \(S(n) = 1 + 2 + \cdots + n\) be the sum of the first \(n\) natural

numbers, and \(C(n) = 1^3 + 2^3 + \cdots + n^3\) be the sum of the first \(n

\) cubes. Prove the following by induction on \(n\):

- \(S(n) = \frac{1}{2} n(n+1).\)

- \(C(n) = \frac{1}{4} n^2(n+1)^2.\)

(BTW, you may find the notations,

\(S(n) = \sum_{i=1}^n i\),

and

\(C(n) = \sum_{i=1}^n i^3\),

to be convenient... or not. It's somewhat a matter of taste.)

- Prove that \(\sqrt{3}\) is irrational.

- For each of the following languages, write down a DFA that

recognizes it. In all cases, we take \(\Sigma = \{0,1\}\)

as our alphabet.

- The set of strings in \(\Sigma^*\) that have \(111\) as a substring.

- The set of strings in \(\Sigma^*\) beginning with the substring \(111\).

- The set of strings in \(\Sigma^*\) ending with the string \(111\).

Suggested exercises: 1.1, 1.2, 1.4b, 1.7a

Assignment #2 (DUE: Tuesday 9/19/19; no collaboration):

- 1.6c, f, g, i

- 1.7c, d, e

- 1.8a

- 1.16a,b

Suggested exercises: 1.4d, 1.11, 1.23, 1.29a,c, 1.46b.

Assignment #3 (DUE: Thursday, 10/10/2019; open collaboration)

- Pg. 84, Exercise 1.6b, d, j.

- Pg. 85, Exercise 1.14.

- Pg. 86, Exercise 1.19b, c.

- Pg. 86, Exercise 1.21a.

- Pg. 88, Exercise 1.29b.

- Pg. 88, Problem 1.31.

- Do not be put off by the length of the explanation in this problem. In fact, once

you read and understand this, rest assured there's actually not a whole lot to do. But it does require a little extra background and

setting up. Please bear with me!

We're going to really prove that the construction of Theorem 1.39 (equivalence of NFA's and DFA's) works. We'll do it carefully, by induction. To do that, we need some conventions and notation first.

Our original NFA is \(N = (Q, \Sigma, \delta, q_0, F)\), where the transition function

\(\delta : Q

\times \Sigma \rightarrow \mathcal{P}(Q)\) takes a single state \(q\) of \(Q\) (given a symbol \(a\)) to a subset \(\delta(q,a)\) of \(Q\). The first thing we'll do is generalize this in a natural way to a function \(\delta : \mathcal{P}(Q) \rightarrow \mathcal{P}(Q)\) that takes subsets of \(Q\) to

subsets of \(Q\). That is, generalize the transition function to mean, for

any set \(R \subseteq Q\),

\begin{eqnarray}\label{delta-def}

\delta(R, a) = \bigcup_{r \in R} \delta(r, a).

\end{eqnarray}

For example, for the NFA of figure 1.31, \(\delta(\{q_1,q_2\}, 0) = \{q_0, q_3\}\)

and \(\delta(\{q_1, q_2\}, 1) = \{q_1, q_2, q_3\}\). The only thing we're doing here is

allowing \(\delta\) to have a set as its first argument. We're adding nothing new to the

behavior of \(N\). (This idea of extending a function to allow subsets

is standard in mathematics.

The set \(\delta(R, a)\) is comprised of the values that \(\delta(r,a)\) can take

on for all \(r \in R\), and is called the image of \(R\), for the given \(a\).

There is, by the way, no reason why we couldn't do this for a DFA as well as an NFA.)

Why is this a convenient notation? Because then the definition of the new machine,

the DFA \(M = (Q', \Sigma, \delta', q'_0, F')\), becomes a little easier to write down,

and it also simplifies the problem.

In particular, the new transition function is just defined by (for any \(R \subseteq Q\), and \(a \in \Sigma\)),

\begin{eqnarray*}

\delta'(R, a) = \delta(R, a).

\end{eqnarray*}

Take some time to understand why this is the case. Study, in particular, Eq. (\ref{delta-def})

above and compare it to the definition of \(\delta'\) in the proof of Theorem 1.39.

(Caveat: I am ignoring \(\varepsilon\)-transitions! If you want to take them into account

in your solution of the problem stated below, please explain how you're doing it.)

The next thing to do is further extend both \(\delta\) and \(\delta'\) to apply to strings,

not just single symbols. For any string \(w \in \Sigma^*\), we

define \(\delta(q_0, w)\) to be the subset of \(Q\) we reach if we begin in the start state

\(q_0\) and read the string \(w\). The analogous definition yields \(\delta'(q'_0, w)\) to be

the state of \(Q'\) we end up in when we begin with the start state \(q'_0\) and read the string \(w\)

(note now I say the state of \(Q'\), because remember \(M\) is deterministic; its

states are only labeled by sets of states of the original machine \(N\)).

With all this said, we are ready to formalize something we can prove by induction. Remember we can

identify each state of \(Q'\) as a subset of \(Q\). With that in mind, the crucial claim is amazingly

simple to state:

Claim: For any \(w \in \Sigma^*\), we have that \(\delta(q_0, w) = \delta'(q'_0, w)\).

Here, then (finally!), is your assignment for this problem:

- Prove the above claim by induction on the length

\(|w|\) of \(w\).

- Show how that claim, in conjunction with all of our definitions here, implies that the NFA \(N\) and the DFA \(M\)

recognize the same language.

Suggested exercises: 2.3, 2.6a.

Assignment #4 (DUE: Thursday, October 31; no collaboration):

- Exercise 1.29b (if you hadn't handed it in for assignment 3, or wish to

have another go at it).

- Problem 1.46c.

- Exercise 2.1a, b. Also these two, not in the text, but I'll call them 2.1e and 2.1f:

2.1e: \(a \times a\)

2.1f: \((a + a) \times a\).

- 2.4b,c,e. For each of these, also state if the language is regular or not, and

justify your answer (doesn't have to be a full proof, but at least indicate

precisely why you

think it's true).

- Write down a CFG that generates all strings over \(\{a,b\}^*\) that

have twice as many \(a\)'s as \(b\)'s.

Suggested exercises: 2.3, 2.7, 2.8, 2.30b.

Assignment #5 (DUE: Tuesday, November 12; open collaboration):

- 2.11

- 2.16

- 2.30a

- Prove that the language \(L = \{0^{n^2} | n \ge 0\}\) is not context-free.

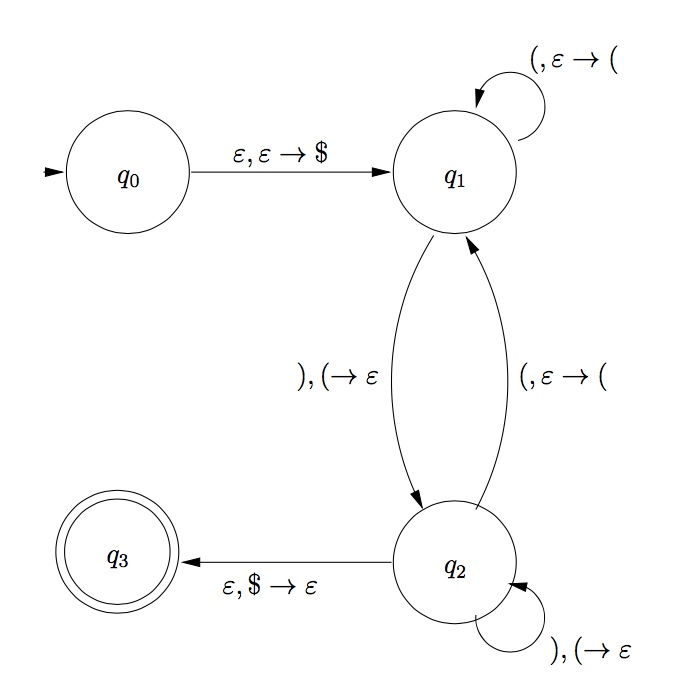

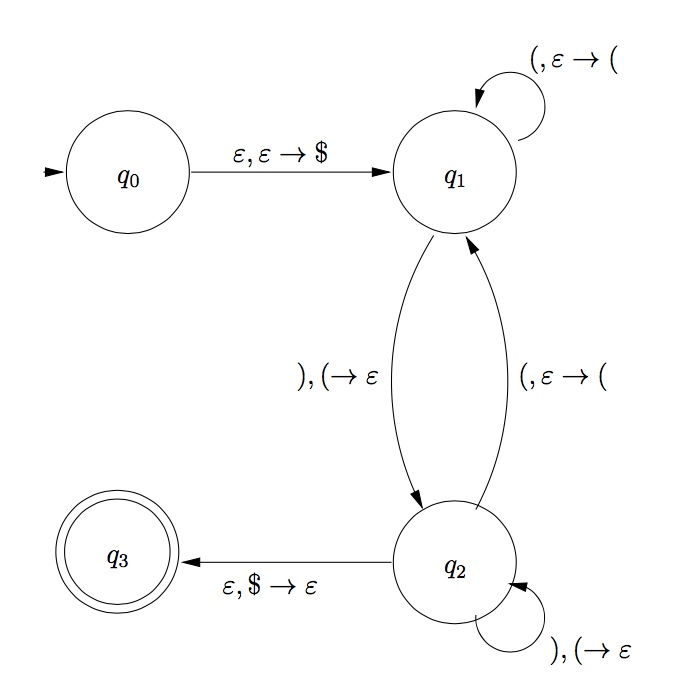

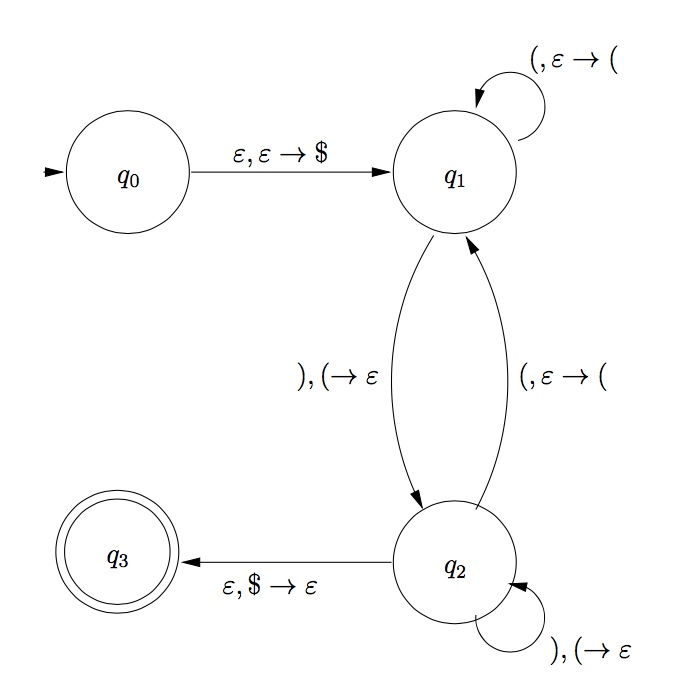

- For the following PDA (which recognizes the language of balanced parentheses), write down a grammar that generates the same language, using

the construction of Lemma 2.27. Using the grammar, write down a parse tree for the

string \((()())()\).

Suggested exercises: 3.1b, 3.2a, 3.3, 3.5, 3.8a

Assignment #6 (DUE: Thursday, November 21; open collaboration):

- 3.1a: For the TM \(M_2\) whose description and state diagram appear in Example 3.7, write down the sequence of configurations that \(M_2\) enters when started on the string just consisting

of the single symbol \(0\).

- 3.2d,e: Similar to the above, for the TM \(M_1\) that

appears in Example 3.9, give the sequence of configurations

that \(M_1\) enters when started on the indicated input string.

For part (d), the input string is \(10\#11\) and for part (e) it is \(10\#10\).

- 3.6: In Theorem 3.21, we showed that a language

is Turing-recognizable iff some enumerator enumerates it.

Why didn't we use the following simpler algorithm for

the forward direction of the proof? As before,

\(s_1,s_2,\dots\) is a list of all strings in \(\Sigma^*\).

\( E = \) "Ignore the input.

1. Repeat the following for

\(i = 1,2,3\dots\)

2. Run \(M\) on \(s_i\).

3. If it accepts, print out \(s_i\)."

- 3.7: Explain why the following is not a description

of a legitimate Turing machine.

\( M_{\mbox{bad}} = \)

"On input \(\langle p\rangle\), a polynomial over

variables \(x_1,\dots,x_k\):

1. Try

all possible values of \(x_1,\dots,x_k\) to integer values.

2. Evaluate

\(p\) on all of these settings.

3. If

any of these settings evaluates to \(0\), accept;

otherwise, reject."

- 3.8c: Give an implementation level description of

a TM that decides the language

\(\{w | w \) does not contain twice as many

\(0\)s as \(1\)s\(\}\).

- 3.15b, c, d, e: Show that the collection of decidable languages is closed under the operations of

(b) concatenation, (c) star, (d) complementation, (e) intersection (HINT: You may use the result of closure under union (which is part (a), solution in text) and

(d) to prove (e).)

- 3.18: Show that a language is decidable iff some enumerator enumerates the language the standard string order.

Suggested exercises: 3.22, 4.1, 4.5, 4.10

Assignment #7 (DUE: Tuesday, December 3; no collaboration):

- 4.3: Let \(ALL_{\sf DFA} = \{\langle A \rangle | A \mbox{ is a }{\sf DFA}\mbox{ and }

L(A) = \Sigma^*\}\). Show that \(ALL_{\sf DFA}\) is decidable.

- 4.4: Let \(A\varepsilon_{\sf CFG} = \{\langle G \rangle | G \mbox{ is a }{\sf CFG}\mbox{ that generates }

\varepsilon\}\). Show that \(A\varepsilon_{\sf CFG}\) is decidable.

- 4.8: Let \(T = \{(i,j,k) | i, j, k \in \mathcal{N}\}\). Show

that \(T\) is countable.

- 4.9: Review the way we define sets to be the same size in Definition 4.12 (page 203). Show that "is the same size as" is an equivalence relation.

- 4.13: Let \(A = \{\langle R,S\rangle | R \mbox{ and } S \mbox{ are regular

expressions and } L(R) \subseteq L(S)\}\). Show that \(A\) is decidable.

Suggested exercises: 5.5, 5.7, 5.10, 5.28 (this last one is quite challenging; it's okay if you don't get it, but do take a look at the solution)

Assignment #8 (DUE: Monday, December 9; open collaboration):

- 5.1: Show that \(EQ_{\sf CFG}\) is undecidable.

- 5.2: Show that \(EQ_{\sf CFG}\) is co-Turing recognizable.

- 5.3: Find a match in the following instance of the Post

Correspondence Problem.

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left\{\left[{{\tt ab} \over {\tt abab}}\right],

\left[{{\tt b} \over {\tt a}}\right],

\left[{{\tt aba} \over {\tt b}}\right],

\left[{{\tt aa} \over {\tt a}}\right]

\right\}

\end{eqnarray*}

- 5.4: If \(A \le_m B\) and \(B\) is a regular language, does that imply that

\(A\) is a regular language? Why or why not?

- 5.9: Let \(T = \{\langle M\rangle | M\) is a \({\sf TM}\)

that accepts \(w^{\mathcal R}\) whenever it accepts \(w\}\). Show

that \(T\) is undecidable.

- 5.17: Show that the Post Correspondence Problem is decidable over the unary

alphabet \(\Sigma = \{1\}\).

Back to CS180 Home Page