Happiness for myself–truly I may as well be more modest and be content if I can only establish hers–as for me I no longer look forward to halcyon days–even under her auspices. My temperament, I know too well, is incapable of allowing me this so-called happiness were it ever attainable by mortal in this world. I am content with nothing, restless and ambitious, and yet scorning the prize within my reach–the fruit of my endeavours seems to me like the fabled fruit of the Dead Sea. Once reached it is but dust and bitterness, and I despise myself for the vanity which formed half the stimulus to my exertions and perhaps leads me to overestimate their values.

Oh would that I were one of those plodding wise fools [Not a wise wish–very possibly I am a fool of another sort without knowing it. Jany. '49.] who having once set their hand to the plough go on nothing doubting, who so long as they only go along care not for the motives by which they are actuated, nor whom they sacrifice to their selfishness.

We met with a hospitable gentleman, Mr Penny, on board the steamer, who invited us to go out to his house the next day, so in the morning we procured horses and rode over to his farm which is about six miles from Launceston. We passed through an exceedingly pretty country, in a high state of cultivation and very like some of the midland counties of England. On all sides of us were fields yellow with the stubble of the lately reaped corn, divided from one another by hedgerows and shady lanes, and here and there might be seen an orchard, the trees absolutely bending down under their weight of fruit. I think that the resemblance to dear old England struck all of us, and all partook of the exhilarating feeling produced by galloping through such thoroughly home scenes. We lounged through Mr Penny's orchard, devoured his fruit, made a very substantial lunch with him and returned to Launceston just in time to dress, and dine with the Mess of the 11th.

We spent a very pleasant evening with them and the next morning started in the steamer back to George Town having compressed into our visit about as much as could well be done in the time. I suppose that bluecoats are rare even hereabouts, for we met with the utmost attention and kindness from everyone.

The next day (March 2nd) we left Port Dalrymple and made a very good run to Goose Island, doing 10-1/2 knots for some hours together–a rate of speed which quite caused a sensation in the old ship. We dropped anchor under the lee of Goose Island in the afternoon and the Captain and a party of us went ashore to view the lighthouse. The island is a strip of granite about two miles long covered with a crust of light soil on which a scanty long coarse grass grows. At one end of the Island is the lighthouse, a fine old tower some eighty feet high. I was exceedingly pleased with the mechanism of the lantern which is of a superior construction. There is a lamp with three wicks in the centre–supplied with the finest oil by a tube leading from a cistern rather above it. By this means the wick is kept constantly fed, the surplus oil flowing over into a reservoir. The mechanism for concentrating the light consists of (1) eight compound lenses (nine pieces?) on the [blank in original] principle. Then to catch all the stray light they have (2) a number (365) of plane plate-glass mirrors fixed at the proper angles for sending the rays out parallel.

[Here, in the original, a sketch of the apparatus.]

The Island is tenanted by Gulls and Mutton Birds, the latter of which as it became dusk flitted about over our heads in immense numbers and rendered walking rather troublesome on account of the immense number of holes they had dug and out of which they rose sometimes like spectres in the gloaming. Besides them there was the superintendent and his wife and children, three convicts and a flock of goats.

The superintendent was away but I had some conversation with this wife–a pretty little woman of some eight and twenty years. She seemed very contented with her lot, said she was never dull as her children of whom there were five kept her hands full. She and her husband had been five years on the island and he was now absent for the first time. ['What do you think of a little establishment of this kind, Nettie darling? Shall I try for a lighthouse. Fancy, you could howl without restrait. Jany. '49.] Their only hardship was that they were sometimes left without food, for which they were dependent upon a neighbouring island, only to be reached in certain states of the wind.

It was dark before we left the island and I had a view of a nebula for the first time through Capt. Stanley's long refractor. It was that in Orion's sword and as the night was remarkably clear I saw it very well, the trapezium of stars being well defined. I could have looked at it for an hour. We had a look at some good double stars as well.

On returning to the ship we found an addition to our ship's company in the shape of a dog, which had swum off from the island. We were lying six-tenths of a mile (the distance was accurately known) from the shore and what could have induced him to leave his old friends and come to us I cannot divine. He swam straight off and then once or twice made the circuit of the ship howling in order to attract attention. When he was seen the jolly-boat was lowered to take him in and now, under the name of "Lighthouse", he is a regular denizen and on account of his good manners a favourite on board. His breed would be difficult to define–he has the head of a Scotch terrier, the body of a turnspit, the legs of a spaniel and a tail altogether anomalous and sui generic.

The next morning we got under weigh and stood on for Swan Island where was another lighthouse to be examined. I did not go ashore here but according to the accounts of those who did, it is much superior to Goose Island. There was evidently considerable vegetation upon it, whereas at Goose Island they had some difficulty in raising potatoes and a cabbage was a chef d'œuvre.

Our westerly wind kept us company till we go away from among the islands, then chopped round and has ever since been easterly and consequently foul, so that we have had the pleasure of being in sight of Cape Howe for the last two days without being able to weather it. I wonder if Job was ever at sea? Every day we are knocking about in these cussed straits is one day lost from Sydney and all that I hold dear therein. If I were a Catholic I would invest a little capital in wax candles to my pet saints, but as it is I have alas no remedy but patience.

I was finishing the drawings for my paper yesterday in the chart room when Capt. Stanley came in, and after looking at my work for some time asked me what I was going to do with them. I told him my plans, when he suggested that I should send the paper to his father who would, said he, "if it were on account of the ship merely, push it to the utmost in the proper quarters". He offered furthermore to write to any one whom I would name and whose influence would be of use in getting it read and printed. All this was purely his own suggestion and indeed I thought he seemed pleased at the idea of sending it to the R.S.

I must say this for the skipper–oddity as he is, he has never failed to offer me and give me the utmost assistance in his power, in all my undertakings, and that in the readiest manner. Indeed, I often fancy that if I took the trouble to court him a little we should be great friends–as it is I always get out of his way and shall do so to the end of the story. That same stiffneckedness (for which I heartily thank God) stands in my way with others, my "superior" officers in this ship, who if I consulted their tastes a little more and my own a little less would I am sure think me what is ordinarily called a "capital fellow" i.e. a great fool. They will understand me I hope' before we part company, though in truth it is a matter of little consequence whether they do or not.

Just now I am on good terms with everybody. No. 1 is absolutely overpoweringly polite, and on M.'s apologising we resumed speaking terms again at Launceston. I kept my word for five months, however, so that he for one, will know that I am "tenax propositi" and not worth offending. How will it be this day six months? ["Haven't quarrelled with a single soul, but I have found it expedient to drop my dearly beloved M. to the outside limits of politeness–be and I are incompatible, but I rather think it is my fault. Jany. '49.] All adrift again I fear, but my equanimity will remain.

[To Mrs. Elizabeth Scott]

. . . I have deferred writing to you in the hope of knowing something from yourself of your doings and whereabouts, and now that we are on the eve of departing for a long cruise in Torres Straits, I will no longer postpone the giving you some account of "was ist geschehen" on this side of the world. We spent three months in Sydney, and a gay three months of it we had,–nothing but balls and parties the whole time. In this corner of the universe, where men of war are rather scarce, even the old Rattlesnake is rather a lion, and her officers are esteemed accordingly. Besides, to tell you the truth, we are rather agreeable people than otherwise, and can manage to get up a very decent turn-out on board on occasion. What think you of your grave, scientific brother turning out a ball-goer and doing the "light fantastic" to a great extent? It is a great fact, I assure you. But there is a method in my madness. I found it exceedingly disagreeable to come to a great place like Sydney and think there was not a soul who cared whether I was alive or dead, so I determined to go into what society was to be had and see if I could not pick up a friend or two among the multitude of the empty and frivolous. I am happy to say that I have had more success than I hoped for or deserved, and then as now, two or three houses where I can go and feel myself at home at all times. But my "home" in Sydney is the house of my good friend Mr. Fanning, one of the first merchants in the place. But thereby hangs a tale which, of all people in the world, I must tell you. Mrs. Fanning has a sister, and the dear little sister and I managed to fall in love with one another in the most absurd manner after seeing one another–I will not tell you how few times, lest you should laugh. Do you remember how you used to talk to me about choosing a wife? Well, I think that my choice would justify even your fastidiousness. . .

I think you will understand how happy her love ought to and does make me. I fear that in this respect indeed the advantage is on my side, for my present wandering life and uncertain position must necessarily give her many an anxious thought. Our future is indeed none of the clearest. Three years at the very least must elapse before the Rattlesnake returns to England, and then unless I can write myself into my promotion or something else, we shall be just where we were. Nevertheless I have the strongest persuasion that four years hence I shall be married and settled in England. We shall see.

I am getting on capitally at present. Habit, inclination, and now a sense of duty keep me at work, and the nature of our cruise affords me opportunities such as none but a blind man would fail to make use of. I have sent two or three papers home already to be published, which I have great hopes will throw light upon some hitherto obscure branches of natural history, and I have just finished a more important one, which I intend to get read at the Royal Society. The other day I submitted it to William Macleay (the celebrated propounder of the Quinary system), who has a beautiful place near Sydney and, I hear, "werry much approves what I have done." All this goes to the comforting side of the question, and gives me hope of being able to follow out my favourite pursuits in course of time, without hindrance to what is now the main object of my life. I tell Netty to look to being a "Frau Professorin" one of these odd days, and she has faith, as I believe would have if I told her I was going to be Prime Minister.

We go to the northward again about the 23rd of this month (April), and shall be away for ten or twelve months surveying in Torres Straits. I believe we are to refit in Port Essington, and that will be the only place approaching to civilisation that we shall see for the whole of that time; and after July or August next, when a provision ship is to come up to us, we shall not even get letters. I hope and trust I shall hear from you before then. Do not suppose that my new ties have made me forgetful of old ones. On the other hand, these are if anything strengthened. Does not my dearest Nettie love you as I do! and do I not often wish that you could see and love and esteem her as I know you would. We often talk about you, and I tell her stories of old times.

To-day, ruminating over the manifold ins and outs of life in general, and my own in particular, it came into my head suddenly that I would write down my interview with Faraday– how many years ago? Aye, there's the rub, for I have completely forgotten. However, it must have been in either my first or second winter session at Charing Cross, and it was before Christmas I feel sure.

I remember how my long brooding perpetual motion scheme (which I had made more than one attempt to realise, but failed owing to insufficient mechanical dexterity) had been working upon me, depriving me of rest even, and heating my brain with châteaux d'Espagne of endless variety. I remember, too, it was Sunday morning when I determined to put the questions, which neither my wits nor my hands would set at rest, into some hands for decision, and I determined to go before some tribunal from whence appeal should be absurd.

But to whom to go? I knew no one among the high priests of science, and going about with a scheme for perpetual motion was, I knew, for most people the same thing as courting ridicule among high and low. After all I fixed upon Faraday, possibly perhaps because I knew where he was to be found, but in part also because the cool logic of his works made me hope that my poor scheme would be treated on some other principle than that of mere previous opinion one way or other. Besides, the known courtesy and affability of the man encouraged me. So I wrote a letter, drew a plan, enclosed the two in an envelope, and tremblingly betook myself on the following afternoon to the Royal Institution.

"Is Dr. Faraday here?" said I to the porter. "No sir, he has just gone out." I felt relieved. "Be good enough to give him this letter," and I was hurrying out when a little man in a brown coat came in at the glass door. "Here is Dr. Faraday," said the man, and gave him my letter. He turned to me and courteously inquired what I wished. "To submit to you that letter, sir, if you are not occupied." "My time is always occupied, sir, but step this way," and he led me into the museum or library, for I forget which it was, only I know there was a glass case against which we leant. He read my letter, did not think my plan would answer. Was I acquainted with mechanism, what we call the laws of motion? I saw all was up with my poor scheme, so after trying a little to explain, in the course of which I certainly failed in giving him a clear idea of what I would be at, I thanked him for his attention, and went off as dissatisfied as ever. The sense of one part of the conversation I well recollect. He said "that were the perpetual motion possible, it would have occurred spontaneously in nature, and would have overpowered all other forces," or words to that effect. I did not see the force of this, but did not feel competent enough to discuss the question.

However, all this exorcised my devil, and he has rarely come to trouble me since. Some future day, perhaps, I may be able to call Faraday's attention more decidedly. Perge modo! "wie das Gestirn, ohne Hast, ohne Rast " (Das Gestirn in a midshipman's berth!).

My birthday again. What an immense change has this twenty-third year made in me! Perhaps taken altogether it will turn out to be the most important of my life. My first year of sea-life–my first year of scientific investigation, the success or failure of whose results must determine my prospects–my first year, last but not least, of love, which has and will model my future life.

I have had a good day of it. First as it happened to be past twelve before I went to bed last night I consider I had a right to read dear Nettie's letters–which I did accordingly and derived great comfort and happiness therefrom. [Rather curious association of your dear letters with a "marine nastiness" you may think, my dearest, but they are more closely connected than you may think. '49.] Secondly– the calm which has existed for some days has allowed many "Buffons" to come to the surface and this morning I was fortunate enough to catch a beautiful "Stephanomia" which was floating quietly along the surface of the blue mirror. I have been very busy examining it all day.

Rockingham Bay

After a tedious voyage interspersed with many calms and contrary winds we anchored at Cape Upstart on the afternoon of the 19th and we remained until three o'clock on the following afternoon for the purpose of taking observations. Twenty-four hours' sail brought us to Gould Island under whose lee we are anchored to-day. Out towards the other shore lies the Tam o' Shanter. She arrived yesterday morning, having parted company with us before we entered the reefs. We have this time taken a peculiar route, entering the Barrier between the Capricorn and Swain's Reefs where there is an opening of some sixty miles width; and from there we have made a straight course up to the Percy Islands.

This passage is altogether outside the other and is considered to be more convenient by the "cognoscenti".

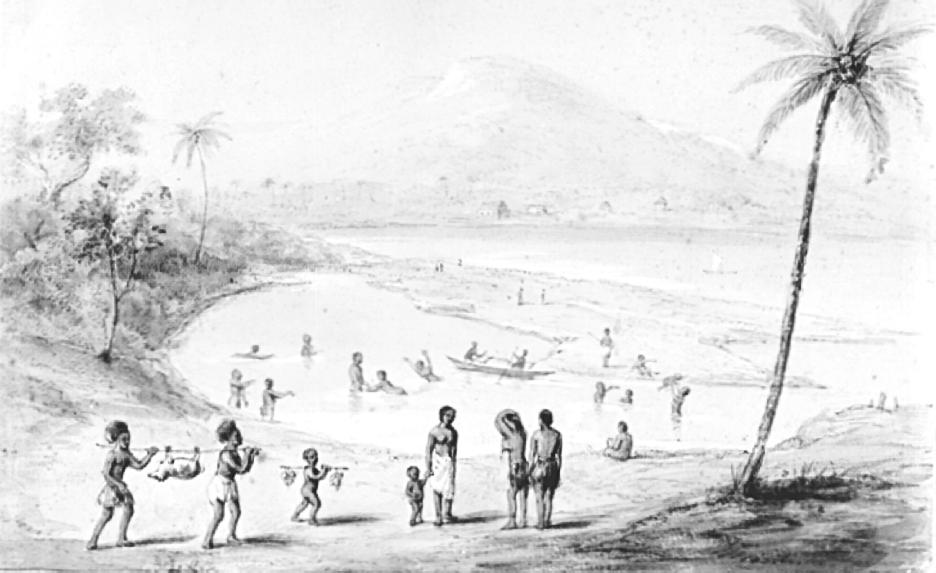

Mount Hinchinbrook is a very fine rugged mass more than two thousand feet high; its summit was enveloped in dense white clouds. Altogether it looked very like Madeira. Three of the natives, an old man and a boy in one canoe and a young man in another, came off to the ship as soon as we had anchored. The old man came on board and was received with due attention of a host of gaping youngsters and Jacks. He seemed very much disposed to make himself at home. He could speak no English but showed great signs of admiration of my white shirt and black neck-ribbon. The canoes of these people are very different from any I have yet seen, though like the others made of bark. These are more neatly made, have a distinct broad and narrow end, either serving however to go foremost indifferently, and are strengthened by ribs of some flexible wood. They paddle themselves along by pieces of bark held in each hand–squatting on their heels rather towards the stern of the canoe so that its afterpart forms a sort of well into which the copious leakage runs. Every now and then they cease paddling with one hand, put it behind them, and bale out, scratching the water out as it were with the paddle. The action is excessively ludicrous. Many of these fellows had a bar of red paint across the bridge of the nose and under the eyes– one had his hair confined in a sort of net like a cabbage net and his beard was done into a flat elongated band fastened together and squared at the end by some white stuff.

[Here, in the original, a small sketch of the man’s head to show the beard.]

These men did not understand the use of a pipe or tobacco. They brought off fish-hooks and lines which they readily parted with for biscuit.

Rockingham Bay

After a tedious voyage interspersed with many calms and contrary winds we anchored at Cape Upstart on the afternoon of the 19th and we remained until three o'clock on the following afternoon for the purpose of taking observations. Twenty-four hours' sail brought us to Gould Island under whose lee we are anchored to-day. Out towards the other shore lies the Tam o' Shanter. She arrived yesterday morning, having parted company with us before we entered the reefs. We have this time taken a peculiar route, entering the Barrier between the Capricorn and Swain's Reefs where there is an opening of some sixty miles width; and from there we have made a straight course up to the Percy Islands.

This passage is altogether outside the other and is considered to be more convenient by the "cognoscenti".

Mount Hinchinbrook is a very fine rugged mass more than two thousand feet high; its summit was enveloped in dense white clouds. Altogether it looked very like Madeira. Three of the natives, an old man and a boy in one canoe and a young man in another, came off to the ship as soon as we had anchored. The old man came on board and was received with due attention of a host of gaping youngsters and Jacks. He seemed very much disposed to make himself at home. He could speak no English but showed great signs of admiration of my white shirt and black neck-ribbon. The canoes of these people are very different from any I have yet seen, though like the others made of bark. These are more neatly made, have a distinct broad and narrow end, either serving however to go foremost indifferently, and are strengthened by ribs of some flexible wood. They paddle themselves along by pieces of bark held in each hand–squatting on their heels rather towards the stern of the canoe so that its afterpart forms a sort of well into which the copious leakage runs. Every now and then they cease paddling with one hand, put it behind them, and bale out, scratching the water out as it were with the paddle. The action is excessively ludicrous. Many of these fellows had a bar of red paint across the bridge of the nose and under the eyes– one had his hair confined in a sort of net like a cabbage net and his beard was done into a flat elongated band fastened together and squared at the end by some white stuff.

[Here, in the original, a small sketch of the man’s head to show the beard.]

These men did not understand the use of a pipe or tobacco. They brought off fish-hooks and lines which they readily parted with for biscuit.

Rain, Rain! The ship is intensely miserable. Hot, wet, and stinking. One can do nothing but sleep. This wet weather takes away all my energies. I do not mind dry heat to any extent but to be steamed in this manner is too much for me. I try to pass the time away in thinking, sleeping and novel-reading, which last is a kind of dreaming. The novel I have been reading is not exactly a first-rate one and yet interested me much as corresponding to and awakening many old thoughts–I could have fancied that I myself had written Ranthorpe.

The author well and clearly points out the difference between aspiration and inspiration, and the fatal wreck that has been made of the lives of those who have mistaken the one for the other. God knows how often the very same thoughts have arisen, how often they do arise, in my own mind. Have I the capabilities for a scientific life or only the desire and wish for it springing from a flattered vanity and self-deceiving blindness? Have my dreams been follies or prophecies? If in old times these questions have pressed themselves painfully upon my mind when my own fate was all that hung in the balance, how shall I cease to think over them now that the fate of one whom I love better than myself, depends upon their right or wrong solution? There is something noble, something holy, about a poor and humble life if it be the consequence of following what one feels and knows to be one's duty and if a man do possess a faculty for a given pursuit. If he have a talent; intrusted to him, to my mind it is distinctly his duty to use that to the best advantage, sacrificing all things to it. But if this capacity be only fancied, if his silver talent be nothing but lead after all–no Bedlam fool can be more worthy of contempt. The man who has mistaken his vocation is lost and useless. He who has found it is, or ought to be, the happiest of the happy.

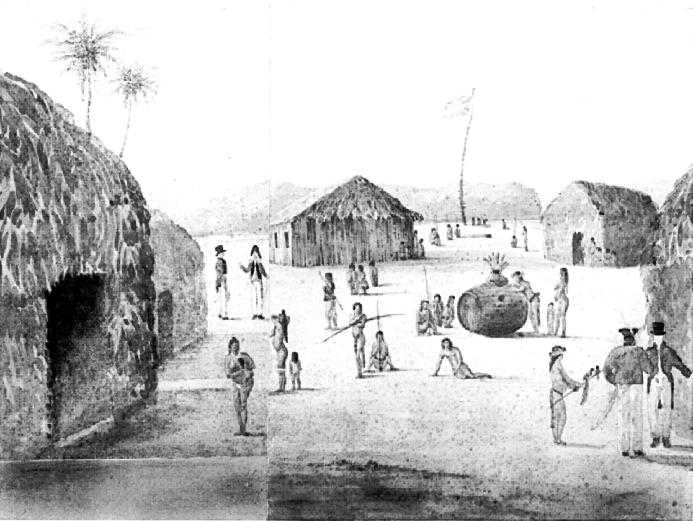

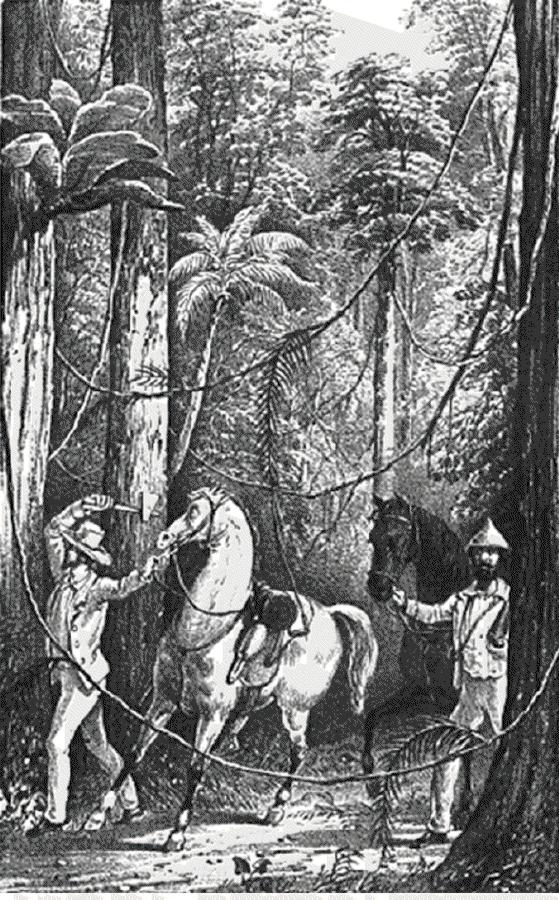

This day week I went away with Kennedy to see his camp at Tam Point. I remained in his tent that night and returned the next day with Capt. Stanley in the galley, but not before I had made an agreement with Kennedy to form one of his light party which was to start for the purpose of feeling the way a little on the morrow. He intended to be away not less than four days or more than six and it was his intention to penetrate thirty or forty miles if possible into the country. I was delighted at the idea of the trip and the little modicum of adventure involved in it–so much so indeed that I found myself up before sunrise the next morning and ready to start with the first cutter which was to convey us down to the camp. Giving our letters into the safe custody of Capt. Marienberg who was to sail that morning, and taking K. on board as we passed, we soon reached the camp. Here we had a capital breakfast à la bush–damper, tea and chops to wit–and by 9 o'c were mounted and off, exploring and no mistake. Our party consisted of Kennedy, myself, and three men–Douglas, Luff, and "Jacky" the blackfellow. Each man had pistols in his holsters and a double-barreled carbine slung by his side, cartridge-belt, and etceteras, so that, though I fear no sergeant would have marched through Coventry with us as "regulars", we should not have been badly equipped for a guerilla raid.

Each man had besides one or two of those inestimable quaint tin pots hanging to his belt–Jacky had his bush axe strapped above his cloak at his saddle bow, and one of the men led a pack horse laden with the eatables, viz., flour, damper, tea, sugar and a little salt pork that I had provided.

"Are you ready?" "All right, sir!" "Come on, then." And we are fairly off into the bush. Kennedy rides ahead, ever and anon taking a bearing with his pocket compass. I follow, somewhat inconvenienced at first by my carbine, and we two beat down the long grass into a road for those who come after us. We go along swimmingly at first but presently we come to a high ridge. We skirt first along one side, then the other, but there seems no end to it. We try to climb it but it is composed of vile loose blocks of stone most unsatisfactory to the shins of the climbers whether man or horse. We find it requisite to halt and Kennedy goes up to the top of the ridge with Jacky and Luff leaving two of us in charge of the horses. He is gone a long time (which I occupy by making studies of the horses in my sketchbook) and when at length he returns it is with rather a long face and the information that the ridge is not to be passed and that if it were the country round about is too thick to allow of passage in that direction.

"Never mind! faint heart ne'er won fair lady" and with that observation venerable at once for its antiquity and its truth, we turned our horses' heads back to the camp, as the day was well spent and no advantage to be gained by bivouacking.

On these as on all other occasions K's only anxiety was on the journey out. When he made up his mind to return, he signified his intention to Jacky who immediately put himself upon our track and led us back like dog following scent.

June 8, 1848

We started again and after one or two ineffectual attempts to circumvent the ridge we gave up the attempt and made our way along the sea beach to the first river. Having reached it we first attempted to follow up its left bank, but fruitlessly, as it was densely wooded with scrub. On this bank we fell in with a party of natives who immediately rushed off in great affright. They had an unfortunate child diseased in some manner so that it could only crawl on all fours. It appeared at first not to be aware of the cause of the sudden departure of its friends but suddenly perceiving us it set up a series of the most unearthly yells and scuttled off as fast it could get along. As we rode along we heard shouts and coo-eys on all sides of us without being able to see anyone. I am free to confess I was not sufficiently used to this to feel quite easy, and began to see that my pistols were handy and occasionally to speculate upon the kind of sensation that would be produced by a spear between the shoulders. But without doubt the poor wretches were far more afraid of us than inclined to disturb us. Still they did not seem to be at all badly inclined for when we returned to the mouth of the river a number on the opposite side held up their arms in sign of peace and pointed out to us the way we should follow in order to ford safely. It was fortunately low water and by keeping close to the line of breakers made by the sea dashing on the bar we crossed without wetting our horses' bellies. As we advanced our black friends retreated and beckoned to us to keep away from them. . . .

Towards noon a strange sail made her appearance to the southward. At first we imagined it must be the Asp but as the stranger drew nearer her different rig undeceived us and gave rise to an infinity of speculations. Some maintained that the stranger was a merchantman's longboat with a shipwrecked crew, some that she was a cruiser bringing us dispatches with immediate orders to move on to China; and speculation was raised to its utmost pitch when somebody boldly asserted the newcomer to be neither more nor less than Want's yacht the WIll o' the Wisp. And old Want became transmogrified into the Flying Dutchman? Or was he taking a mad cruise merely? Had he probably as much champagne as usual on board? Or was it Col. Barney coming to form a new indefinite settlement somewhere? or – or–or––?

To solve all these queries the second galley was dispatched to board the vessel. She returned speedily and raised us to a pitch of excitement "such as was not recollected by the oldest inhabitant" by a tale of natives and attacks and wounds and distressed crews.

But what was said I do not well know as I was in the galley in five minutes laden with lint and bandages, with thoughts of amputation and fractures in my head, and pulling like mad towards the vessel which in the meanwhile had anchored close to us. On arrival I was speedily ushered below where I found Roach, the skipper, lying half insensible with a very severe wound of the head, plastered up as best might be.

And when I had attended to him I found that one of the crew, a New Caledonian, had received even worse injuries in the same quarter, but thanks to his good constitution or the thickness of his skull, he seemed to be not in the slightest degree inconvenienced.

It appeared that the vessel had been dispatched from Sydney to search for sandal-wood among the Islands off the coast, and that on the 22nd (Monday) she anchored under one of the Palm Islands. The skipper and some of the crew went ashore and fell in with many natives who appeared to be very friendly. They brought off two and showed them the vessel. It is noted in the Captain's log that they noticed only two things–an accordion and some axes which latter they were very desirous to possess. There can be little doubt that the iron articles were in fact the cause of the subsequent attack. However, the two natives were well treated and dismissed, and the crew suspecting nothing went to rest. The middle watch seems to have fallen to Sam, the black. He had gone below for some purpose or other about half-past three in the morning, when the vessel was surrounded by five or six canoes containing about thirty natives, armed with waddies and boomerangs and carrying pieces of lighted bark. They seem to have planned their attack well, for they stationed four of their party over the fore hatchway and two over the after one, ready to strike down anyone attempting to ascend, and then they threw some of the lighted bark down into the cabin –apparently for ferretting out the unfortunate occupants à la Pelissier. In the meanwhile the noise had aroused the skipper and Sam, both of whom were leaping up on deck when they were struck down by the boomerangs of the niggers above. But the mate had contrived to get hold of a cutlass and watching his opportunity he thrust one of them through the body, leaped on deck and commenced laying about him to some purpose. And he was speedily seconded by the crew, who by this time had ferretted out their pistols. One black-fellow fell back shot through the throat and in falling overturned his canoe and those who were in it. Of the rest some were killed, some wounded and the rest shoved overboard, and the decks once clear the crew got their little swivel gun loaded and let drive–into the midst of the fugitives. They had now time to attend to the Captain and Sam who lay helpless, and having plastered up their wounds as they best might they made sail, and stood on for Gould Island. Here, a similar fate seems to have awaited them. They were obliged to water and for this purpose the four available hands went ashore in their little whale-boat, armed to the teeth. They had hardly got their breakers ashore, before they saw a considerable body of natives putting off towards the vessel, this time in the ordinary small bark canoes. They were determined not to subject themselves to another attack so they immediately shoved off, pulled between the enemy and their vessel and then fired away. The gentlemen in black, unprepared for such a warm reception, vanished much faster than they came.

Cursing such inhospitable shores they once more made sail and on the Thursday morning fell in with our boats who directed them to us.

The whole cause of the attack at the Palm Islands seems to have been the iron which the natives saw in the vessel, for they contrived to carry away the pump spears [?], and a hatchet was found concealed in one of the canoes they left behind.

At anchor under Lizard Island. Read through the first canto of the Divina Commedia this evening. Have not the impudence to say that I thoroughly understood all of it. Since I began Italian I have read (1) the first part of Sforzi's Storia Romana, then (2) Il Cortegiano Questo, then (3) L'Avare & Tartuffe in Italian, then Le Cerimonie, then L'Arta Poetica of Metastasio (or rather of Horace) besides some of his Canzones and letters. Somehow or other Italian does not seem to come home to me as German does. The elegant smoothness seems cold compared to the glorious rugged "seelenvoll" old Saxon Deutsch.

Finished reading the Inferno. I began Dante with the Paradiso but after getting through some seven cantos I found that, what between the obscure reasonings and the difficulties of style, I made no great progress. So I turned to the Inferno which is indeed the natural commencement and read a canto every evening or thereabouts. Dante must employ a great variety of words for in the early cantos there were on an average about 30 words new to me in every canto; and the number did not sensibly diminish till I reached the 27th or 28th canto. I think I now understand all, except of course some of the historical allusions which could only be intelligible to one well up in the history of the times.

Certainly I understand it enough to enjoy it. All imperfect as my knowledge of the language is I can appreciate the wonderful graphic power of his descriptions.

He describes Hell like a practical Times reporter, sparing no detail however hideous and caring not how homely his comparisons may be so long as they are but apt. I think I never read anything so horribly distinct as his description of the Metamorphosis in Malebolge or those poor Popes with their writhing soles burning like "cose unte" and then Francesca da Rimini and the Count Ugolino with his "Anselmuccio mio" and that splendid sketch of a devil "sovrà il piè leggiero" in a verse of the 21st Canto. I don't wonder at the Italian women thinking that he had actually been down to Hell, for I have sometimes been half inclined to think the book not quite "canny" myself.

I have been getting very apathetic of late, and I think I never was so mortally sick or anything as of this wearisome monotonous cruise. I care for little else but sleep, and I have a great mind to coil myself up and hybernate until we get letters at Cape York. Another week, thank Heaven! must bring us there.

We are laying at present under Sunday Island, a kind of repetition in miniature of Lizard Island. I have not been ashore and don't care to go, what's more.

"Wookduoo"

What has the year 1848 done for me? is a question I may well ask, and yet perhaps may not find the true answer these ten years. What have I done for it? All too little. I have spent time that should have been occupied with work in idleness, that should have been occupied with grateful recollecitons in foolish discontent at the present and still more foolish anticipation of the future, and yet as poor Gretchen sings:

Alles was dazu mich trief

Ach! war so schön,

Ach! war so lieb . . .

So true it is that the growth of our virtures involves that of our faults also, and the very circumstance that prompts my better actions is a source of discontent and vain regrets. Dearest Nettie, this time last year I had known you well but for one short week and I had received but one letter from you. Then as now I expected that the two or three weeks would once more bring me to your side, then as now the fever of warm anticipation possessed me, but in one sense how much happier am I now. Then it seemed a dream, now I have a "sober certainty of waking bliss"; then I hoped you were what I wished you to be, now I know it. If time would but confirm as accurately all my instinctive beliefs I should make a famous seer.

|

THE

HUXLEY

FILE

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||