[To Mrs. Rachel Huxley]

(After describing how he had just come back from a nine months' cruise)–First and foremost, my dear mother, I must thank you for your very kind letter of September 1848. I read the greater part of it to Nettie, who was as much pleased as I with your kindly wishes towards both of us. Now I suppose I must do my best to answer your questions. First, as to age, Nettie is about three months younger than myself–that is the difference in our years, but she is in fact as much younger than her years as I am older than mine. Next, as to complexion she is exceedingly fair, with the Saxon yellow hair and blue eyes. Then as to face, I really don't know whether she is pretty or not. I have never been able to decide the matter in my own mind. Sometimes I think she is, and sometimes I wonder how the idea ever came into my head. Whether or not, her personal appearance has nothing whatever to do with the hold she has upon my mind, for I have seen hundreds of prettier women. But I never met with so sweet a temper, so self-sacrificing and affectionate a disposition, or so pure and womanly a mind, and from the perfectly intimate footing on which I stand with her family I have plenty of opportunities of judging. As I tell her, the only great folly I am aware of her being guilty of was the leaving her happiness in the hands of a man like myself, struggling upwards and certain of nothing.

As to my future intentions I can say very little about them. With my present income, of course, marriage is rather a bad look out, but I do not think it would be at all fair towards N. herself to leave this country without giving her a wife's claim upon me.... It is very unlikely I shall ever remain in the colony. Nothing but a very favourable chance could induce me to do so.

Much must depend upon how things go in England. If my various papers meet with any success, I may perhaps be able to leave the service. At present, however, I have not heard a word of anything I have sent. Professor Forbes has, I believe, published some of MacGillivray's letters to him, but he has apparently forgotten to write to MacGillivray himself, or to me. So I shall certainly send him nothing more, especially as Mr. MacLeay (of this place, and a great man in the naturalist world) has offered to get anything of mine sent to the Zoological Society.

... I suppose you have wondered at the long interval of my letters, but my silence has been forced. I wrote from Rockingham Bay in May, and from Cape York in October. After leaving the latter place we have had no communication with any one but the folks at Port Essington, which is a mere military post, without any certain means of communication with England. We were ten weeks on our passage from Port Essington to Sydney and touched nowhere, so that you may imagine we were pretty well tired of the sea by the time we reached Port Jackson.

Thank God we are now safely anchored in our old quarters, and for the next three months shall enjoy a few of those comforts that make life worth the living....

The only place we have visited since my last budget to you was Port Essington, a military post which has been an object of much attention for some time past in connection with the steam navigation between Sydney and India. It is about the most useless, miserable, ill-managed hole in Her Majesty's dominions. Placed fifteen miles inland on the swampy banks of an estuary out of reach of the sea breezes, it is the most insufferably hot and enervating place imaginable. The temperature of the water alongside the ship was from 88 to 90, i.e. about that of a moderately warm bath, so that you may fancy what it is on land. Added to this, the commandant is a litigious old fool, always at war with his officers, and endeavouring to make the place as much of a hell morally as it is physically. Little more than two years ago a detachment of sixty men came out to the settlement. At the parade on the Sunday I was there; there were just ten men present. The rest were invalided, dead, or sick. I have no hesitation in saying that half of this was the result of ill-management. The climate in itself is not particularly unhealthy. We were all glad to get away from the place.

[To Mrs. Elizabeth Scott]

By the way, I may as well give you a short account of our cruise. We started from here last May to survey what is called the inner passage to India. You must know that the east coast of Australia has running parallel to it at distances of from five miles to seventy or eighty an almost continuous line of coral reefs, the Great Barrier as it is called. Outside this line is the great Pacific, inside is a space varying in width as above, and cut up by little islands and detached reefs. Now to get to India from Sydney, ships must go either inside or outside the Great Barrier. The inside passage has been called the Inner Route in consequence of its desirability for steamers, and our business has been to mark out this Inner Route safely and clearly among the labyrinth-like islands and reefs within the Barrier. And a parlous dull business it was for those who, like myself, had no necessary and constant occupation. Fancy for five mortal months shifting from patch to patch of white sand in latitude from 17 to 10 south, living on salt pork and beef, and seeing no mortal face but our own sweet countenances considerably obscured by the long beard and moustaches with which, partly from laziness and partly from comfort, we had become adorned. I cultivated a peak in Charles I. style, which imparted a remarkably peculiar and triste expression to my sunburnt phiz, heightened by the fact that the aforesaid beard was, I regret to say it, of a very questionable auburn–my messmates called it red.

We convoyed a land expedition as far as the Rockingham Bay in 17 south under a Mr. Kennedy, which was to work its way up to Cape York in 11 south and there meet us. A fine noble fellow poor Kennedy was too. I was a good deal with him at Rockingham Bay, and indeed accompanied him in the exploring trips which he made for some four or five days in order to see how the land lay about him. In fact we got on so well together that he wanted me much to accompany him and join the ship again at Cape York, and if the Service would have permitted of my absence I should certainly have done so. But it was well I did not. Out of thirteen men composing the party but three remain alive. The rest have perished by starvation or the spears of the natives. Poor Kennedy himself had, in company with the black fellow attached to the party, by dint of incredible exertions, pushed on until he came within sight of the provision vessel waiting his arrival at Cape York. But here, within grasp of his object, a large party of natives attacked and killed him. The black fellow alone reached Cape York with the news. The other two men who were saved were the sole survivors of the party Kennedy left behind him at a spot near the coast, and were picked up by the provision vessel when she returned.

You may be sure I am not sorry to return home. I say home advisedly, for my friend Fanning's house is as completely my home as it well can be. And then Nettie had not heard anything of me for six months, so that I have been petted and spoiled ever since we came in.... As I tell her I fear she has rested her happiness on a very insecure foundation; but she is full of hope and confidence, and to me her love is the faith that moveth mountains. We have, as you may be sure, a thousand difficulties in our way, but like Danton I take for my motto, "De l'audace et encore de l'audace et toujours de l'audace," and look forward to a happy termination, nothing doubting.

Our previous discomfort enables us to appreciate with double force the exquisite weather we are now enjoying. Nothing can be more beautiful than this smooth sea, just sufficiently broken into waves to give an appearance of life to the deep blue waters; this deep infinite blue sky, with here and there a summer cloud floating dreamily along, or hanging like a hovering bird, realizing that exquisite simile of Joanna Baillie's:

Even the old ship looks well with her pile of canvas just distended by the soft gentle breeze. At night she looks ghostly, the bright moon lights up the white sails, vague shadows from the rigging and spars play over their surface, and the darker outlines of the masts fade into the surrounding shade. The canvas looks like a self-supporting cloudy pyramid. At that time when the sleepy watch, weary of doing nothing, dozes away in imaginary wakefulness, I walk the deck. And I am not solitary for a thousand thousand thoughts chase one another through my brain. And strangely enough with whatever subject I commence, you, dear one, invariably become at last directly or indirectly the object of my meditation.

Or I lean over the gangway and look down into the dark shadow of the ship. The little waves plish-plash with a pleasant murmur against the side, and the light-sparkles dance and glimmer away for a brief moment and then are no more seen. Dreamy parables do these waves murmur in one's ears. That great sea is Time and the little waves are the changes and chances of life. The ship's side is Trouble, and it is only by meeting with this that the little creatures in the water shine and grow bright. They are men. If it were calm they would not be bright. See, there is a big one; he shines like a fiery globe. He is some great conqueror. He keeps on shining for full a minute–that is Fame–and then gives place to darkness like the rest. Oh brave! who would not be great!

SOMEBODY: "Well, what are you thinking about ?"

SELF: "I was merely looking–to–to see what she is going– "

[SOMEBODY:] "Oh, two and four; bother it, I hate this lazy work."

SELF: "Hum: I rather like it." A pause.

SOMEBODY: "Well, aren't you going to have a walk?"

SELF: "No - a - thank you - a - I'm tired."

SOMEBODY: "Unsociable fellow that is." Exit.

SELF: "Thank God, that frump's gone."

If I had been Robinson Crusoe I certainly should never have been troubled with his yearnings after society, or else the mass of men are very different from those whom I have seen. And yet I believe they are as good as the mass and certainly quite as good as myself. The only reason why I prefer my own society to that of other people is, that–I am not obliged to regard my own follies as wisdom, or look as if I did, which is as bad. I can call myself a fool and believe it too, and offend no one.

The air is hot and damp, the sky cloudy and frequently it rains. My cabin resembles an orchis-house and I sit melting though half stripped. I have a sort of presentiment that this style of thing will endure for the next four months. Woe! Woe! to them that be fat [?]. Our course is peculiar. No longer we can see we go towards our goal, but at night we shorten sail and "revenons sur nos pas", till daylight, whereby our total progress is not the sum but the difference of our nocturnal and diurnal progression.

I am becoming a very morose animal, worse than I was last cruise I think. I feel inclined to avoid everybody, and to shut myself up in my own pursuits.

It annoys me at times to hear others talk, and I could sometimes bite anybody who speaks to me. Why this should be I can't tell, and I tell myself that it is very unreasonable–foolish–wrong, etc. All of which preachment has the usual effect of admonition.

I feel like a tiger fresh caught and put into a cage.

Early this morning we sighted the Presqu'ile Condé (?) a point of land on one of the Islands to the southward and westward of C. Deliverance.

The land appears high and varied in outline. All day it has been overhung and obscured by dense clouds, frequently pouring down rain, sometimes one portion only being visible, sometimes another according as the cloudy canopy shifted. We have not been near enough to form any idea of the character of the country, though with this amount of heat and moisture it must be sand itself to be otherwise than fertile.

June 13, 1849

To-day we stood in towards the land early in the morning and preceded by the Bramble made our way round the north end of Rossel Id. and thence along the Récif Rossel which stretches for some 30 miles to westward of the island, in the hope of finding a harbour on the W. side of the island and to the S. of the reef. But the sun set before we were very far round the end of the Recif Rossel and so we are hove to for the night. During the whole of the morning we were not more than two miles distance from the N. shore of Rossel Id, so that one could form some notion of the country. It is a beautiful island, with its surface diversified by numerous peaks and vallies, and clothed with verdure from the sea-shore to the top of the mountain peaks. And the verdure too is none of your green-brown Australian foliage, but a deep-coloured, rich, leafy mass, of all shades from indigo to grass green. Half a mile or so from the shore runs a narrow white line of surf marking the position of the fringing reef which, alas for our chances of finding a harbour, runs like a natural defense parallel to the coast. Within this is a space of deep blue water, contrasting beautifully with the sandy beach where such exists. But for the most part the shore was mangrovy.

Groves of cocoa-nut trees were to be seen here and there and "matted" among them, to quote a favourite expression of Brierly's, were usually one or more huts, usually in the shape of a barrel cut in half, i.e., low and arched and steep at each end. Not very far from the huts and cocoa-nut patches one might occasionally see a clear patch of land exhibiting many parallel rows of something or other, concerning which a great controversy has arisen, some maintaining them to be cleared and cultivated fields, planted in rows like any dibbled farmground, others, that it is a mere natural result, a sort of lusus naturae. But as the lusus-party don't allege how nature has played such tricks, in any feasible manner, and as I fear they are somewhat actuated by the spirit of opposition. I incline to the cultivation-party, and it down as a fact: "The Louisiadians cultivate the Ground ".

We saw natives on the beach and parties of them engaged in fishing close to the reef, burt they were too far off to make out their ugly mugs. Some of the canoes had large lateen sails. I hope we shall be nearer neighbours.

Boats out sounding to find us a new anchorage nearer the land. We saw seven or eight canoes with 8-10 men in each, but none of them would come near us. Several however went to the Bramble. I suppose they thought she was smaller and less able to do them harm.

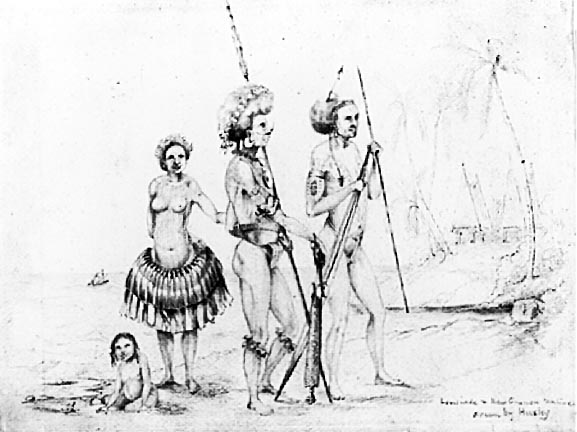

They had some of them the large bushy heads of hair of the Papuans but others were without this distinctive mark and they varied considerably in colour. For the most part they were coppery. The canoes have a single outrigger and a good deal resemble those we saw at Cape York. The sail consists of three sheets of some fibrous substance, and shortening sail is performed by taking down each sheet separately and laying it along the gunnel. The upper end of each sheet has a great many little pennants streaming from it.

The paddles are something like the ace of spades with a long handle. They sail up near to the place they wish to reach, then strike sails, masts and all, and paddle up. The only articles of barter they brought to the Bramble were yams, cocoanuts and tortoiseshell. They were very greedy for iron and stole one of the crutches wh. happened to be lying loose on the thwart of a boat astern. Like any dexterous London thieves they passed it from hand to hand and concealed it at the far end of their canoe, and when charged with the theft looked as innocent and impassive as M. de Talleyrand himself could have looked under similar circumstances.

But when from the threatening attitude the Brambles put on they saw it was "no go" they passed the crutch over again and paddled off as hard as they could paddle–more ashamed of the failure than the theft, I fancy.

At one o'clock Simpson was sent away in the cutter to look after a watering place and Henderson to open communications with the natives. I among others accompanied him.

A number of natives were fishing on the reef adjoining the small green island and thither we first betook ourselves. They were fishing, some with spears and others with a large sort of seine, but on our approach all their occupations were given up and in spite of the most enticing offer of red cloth etc. they betook themselves to their canoe and made off for the land waving towards it as if inviting us thither.

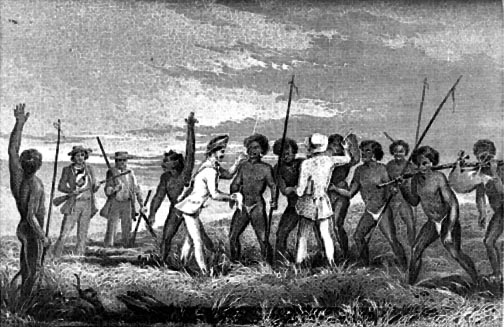

As a reef stretches between the small green island and the larger island on which are the huts, we could not follow them, but we landed very considerably more towards the ship. To use a paddyism we landed in the water, as the lumps of coral and rock would not allow of the boats grounding on the shore, thereby getting considerably damp and spoiling our shoes. Our fishing friends had in the meantime also landed and as soon as they saw us on this territory they advanced slowly towards us–one bright copper-coloured gentleman who appeared like Paul to be "the chief speaker" bearing a green branch in his hand which he frequently waved. We too gathered branches and waving for the dear life and making all sorts of unearthly noises, supposed to express our pacific disposition, went towards them.

At some forty yards distant however, our coppery friend halted and made very significant signs to us to be off about our business, and when we continued to advance, he and his people retreated. At last McGillivray, leaving his gun with us and taking a branch in each hand, went jumping and dancing with all sorts of antics towards them. They allowed him to come up but still seemed disinclined for our society.

Brierly then took upon himself to do the agreeable and advanced in the same way but with such wonderful antics that the niggers seemed irresistibly attracted and committed themselves to several acts of barter. After a little while, laying my gun aside I went to them, and had a very interesting and polite interview with friend coppery and two other gentlemen who were quite black and had large fuzzy heads of hair with combs a foot long, narrow and very long-pronged, stuck into the front of their very remarkable coiffure.

Brady had given me a red cap which was much coveted by all, but I made one of the fuzzy-headed gentry give me an ornamented chunam-gourd for it. Some waste paper procured me one of the long combs.

I made a hasty sketch of the most remarkable of the fuzzy heads, but in spite of all my attempts to be amusing he was off before I could finish it.

These men vary considerably in colour and appearance. Some of them are as black as the Australians and these appeared to me to be fuzzy-headed; others again were of various shades of copper colour and these appeared to have close short hair. Their only clothing was a long leaf curled up behind into a most absurd appendage like a bustle. Their teeth were stained red by the betel. They mostly carried baskets, containing various odds and ends, gourds containing chunam etc.

They had no arms of any description with them. The chief demand was for cloth, especially red cloth. Buttons were heavy on hand. Iron on the other hand at a great premium, to judge from the avidity with which they clutched at a penknife I accidentally took out. But I would not part with it as it was my only one, much to their disappointment.

Many wore circular ear-rings apparently made of the operculum of a Turbo ground flat and cut to the centre so as to allow of the pierced lobe of the ear being passed in. And the septum of the nose was ornamented–save the mark!–with a long white bone or some such thing stuck through it. They wanted us to go up to their village but the want of time obliged us to decline, and we betook ourselves along the beach in the opposite direction to look for water. The rock was slaty, and its fragments mingled with sharp and jaggy fragments of coral did not make a pleasant surface for walking, particularly considering the softened and pappy state of our shoes.

We passed several clumps of cocoa-nut trees and luxuriant brushes, the soil where bare of trees being covered with long silky grass, but we found water only at one place and there in small quantity. The cutter accompanied us along the shore and at the western point of the island we waded off again and got on board.

The only birds I saw were parrots, a white cockatoo and some kingfishers. There was a queer little leaping fish (Chironectes) with large pectorals, in the mud.

On the I7th (Sunday) Simpson and Heath went away in the cutter to examine the other (western) side of the island on which we landed on Saturday for the purpose of finding anchorage and watering place. McGillivray, Brierly and I accompanied them. We kept outside the small islet with the reef that stretches from it to the island and as we advanced towards the N.E. end of the island seeing natives (some of them with green branches) making their way over the hills and waving to us, we landed. The water shoaled so that the cutter was unable to approach within some fifty yards or so of the shore, so tucking up our duds, and looking well to our "ammunition of war", Simpson, McGillivray, Brierly and I waded to the beach. This was a narrow strip of sand behind which there was a steep grassy ascent, clothed abundantly with trees. By the time we had landed a number of the natives had arrived at the top of the ascent and were hullaballooing at a great rate.

We ascended to meet them and they incontinently retired, leading us over the tops of the hills, and through the luxuriant long grass, for about a quarter of a mile. Our coppery friend of the preceding day was of the company, but he did not seem much inclined to trust us, and the whole party went jogging on until they were joined by a good many more who came over the hills armed with their spears; by this time there were some 30 or 40 natives, almost all with their spears, and one had a carved and pointed wooden sword. This gentleman from his extreme blackness and ugliness and the peculiarity of his weapon was immediately named the "Jack of Clubs".

It was now our turn to be cautious, and without advancing any further we tried to do a little barter for their ornaments etc. But the market was decidedly dull. They seemed to have a very distinct notion of getting but no idea of giving, and they began to get round us (Brierly and I, Simpson and McGillivray keeping a look out as rear-guard), pulling and snatching at anything that took their fancy. Suddenly we heard a squeaking, and two blackfellows came over the hill at a great rate bearing an unfortunate pig slung over a pole. This they cast down at our feet, and taking a knife from me and a handkerchief from Brierly, seemed to wish us to understand that we had better be off at once. We were delighted to get the pig and immediately shouldered it and began to march off, chuckling immensely at our success, when I missed a pistol which I had stuck in my belt.

I did not at all like the idea of losing this, so I dropped the pig and went back making signs that I wanted it, as I had no doubt that it had been stolen by some of the blackguards. They pretended to look about in the grass for it, and when, disgusted at this sort of humbug, I looked big and blustered a little, they drew together and scowled, handling their spears. It was quite evident this game would not do, and so I pretended at last to be satisfied, and forming in battle-array, Simpson as advanced guard, Brierly and I carrying the pig, and McGillivray as rear-guard, off we marched, not without keeping a sharp look out on the gentry behind, who were evidently not [at] all well disposed. I was ready to die with laughing at the absurdity of the scene, more especially when we adopted the expedient of sliding down the high bank before mentioned, pig and all, as the quickest mode of reaching the boat. While piggy and his carriers, squealing and laughing, slid, Simpson and McGillivray kept a look-out at the top of the bank as some of the riggers were gliding off by twos and threes into the thick wood upon its side, and it would not have been a satisfactory place to have been attacked in. However we all got safe into the boat with our prize. The natives had pointed us out a deep ravine leading into a bay on the N.W. side of the Id., which they indicated to contain fresh water, and so we went round to examine it.

There was very good anchorage, but a reef stretched off so far from the shore that it would have been impossible to water the ship, as the boats would have been unable to get over it. The bay was very beautiful, with abundance of cocoa-nut trees, and towards one end there were several huts. We were not near enough to examine them clearly, but it appeared to us, with the glass, that the affairs on posts were really huts mounted up and not mere canopies.

After leaving the bay we stood over to a small thickly wooded island, where we anchored during the dinner hour. We landed and wandered over the island in quest of game. There were no inhabitants, and it altogether resembled one of the small Australian islets. There was the Casuarina, and a thick brush in which we found several Megapodius mounds. McGillivray shot a Megapodius identical with the Australian sp.

There seemed to be a clear passage out between the islands on this side.

When we returned to the boat we saw a canoe approaching under sail. There were eight or nine copper-coloured natives in it, and they steered straight for us, showing none of the distrust the others had manifested. We procured some very good cooked yams and a spear from them and they then went quietly to fish off the reef.

We returned to the ship by about half-past four.

Several canoes came off this morning; one of them brought the figure-head which was so much wanted yesterday, and bartered it immediately. In one of the canoes was a man with a jaw bracelet. The jaw was in fine preservation and evidently belonged to a young person, every tooth being entire. They seemed to have no scruple in selling it. A jade hatchet was procured from them also.

In the middle of the day we weighed and stood over to our present anchorage, close to S.W. Island.

|

|

Jawbone Bracelet |

Fishing Hooks |

| MacGillivray, Narrative | |

| I.216 | I.198 |

The master had found a watering place here previously and today I went up m one of the cutters. Passing over a bar you enter a narrow river bordered on each side by very high mangroves. As you go further up and the water becomes fresher these become less and less frequent, trees of all sorts arch overhead and spreading their branches across the stream impede your progress. Cutting and dodging and breaking boughs, putting the helm hard a-port to avoid this snag and hard a-starboard to get out of the way of that dead and fallen tree, you work your way up for about a mile, when suddenly turning a corner you see the water tumbling over a small rocky ridge which extends across the stream. The surrounding brush is very beautiful at this point. A dense dark mass of foliage stretches up into the sky in front, here and there relieved by the graceful bright feathery heads of palm trees or the fantastic shapes of the Pandanus, which here grow to the height of sixty feet or more, with its long pillar-like roots forming a pyramid 15-20 feet above the ground.

There were many tree-ferns about this spot too with beautiful finely-cut fronds and sculptured stems.

I tried to make a drawing of the place, but it disgusts me exceedingly compared with my remembrance of the reality.

We found a Megapodius mound and one was shot, and there were reports of traces of wild pigs.

Four or five canoes full of niggers, mostly old friends, came off to us today, from somewhere about Pig Id. Barter very active for iron. A thing like a kneading pan was procured. One old gentleman had lost his nose, which imparted an expression of soft and pleasing melancholy to his countenance.

|

THE

HUXLEY

FILE

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||